"The depression took its toll on Daddy," Mama told me one day with tears in her eyes. "It crushed his pride, forced him to accept day labor. He's never been afraid of hard work, and would take any job offered him. Money earned from a few hours of digging ditches sometimes fed our family for a week."

The bank foreclosed on the first house he built for his family and after that experience he never again asked a bank for credit. He was an electrician by trade, but for years after the foreclosure there still was little work to be had in the South.

Some mornings Daddy followed the streetcar line over the mountain to town, picking up discarded soft drink bottles along the way. He'd redeem the bottles, spend his windfall on as much day-old bread as he could carry, then hike back home, a tired but grateful man. And for the next few days our family would have toast with our oatmeal.

While work was scarce Daddy raised chickens, goats, hogs and cows in pens on the hill behind our house. He turned the earth in a flat plot of ground above the outhouse with a shovel and carefully pressed corn and bean seeds into the rich soil. When the vegetables matured, all the relatives who lived nearby helped Mama can green beans, tomatoes, and soup mix, which all the families shared.

In Daddy's spare time, he made a rope swing, a see-saw, and a spinning Jennie for us from other people's discards. He took great pride in his work and we admired his ability to make something for us from practically nothing.

He raised pigs, cows chickens and goats. Twice a day Daddy milked the cow. I’d wait for him to finish milking, then follow him into the kitchen with the brimming bucket of rich, warm milk. To this day, I miss drinking warm milk straight from the cow.

By the time school got out for the summer of 1941 our family’s financial situation had greatly improved. Daddy had steady work, with paid overtime, and offered to buy Mamma a new car if she would learn to drive.

The two of them didn’t let us in on the plan. Three times a week Mamma would put on her Sunday best, send me to play with my cousin, and walk out to the streetcar line, refusing to tell us where she was going all dressed up.

Then one day she came back all smiles, a new driver’s license clutched in her hand. The next day she and Daddy drove off in his old Graham Page to buy a new car. She came home driving the shiny, navy blue 1941 Dodge sedan with Fluid Drive she drove until 1949.

Since it looked like Daddy’s job in Childersburg, Alabama would last a while, right before school started we moved to Vincent, Alabama to end his twice-daily thirty mile commute. Vincent was an old cotton-growing settlement across a wide river from Childersburg, where DuPont was putting up a gunpowder plant and Daddy was foreman over all the electrical work.

I would soon be eight, and my memories of Vincent are quite clear. Hitler and his men were shooting at everything in sight in some places my teacher pointed out on a map, increasing the need for gunpowder. That part was good, because it gave Daddy steady work, but a gunpowder plant is a very dangerous place to work and we worried about him.

Once we were settled, Daddy drove us out to the ferry landing to show off the muddy water he was ferried across twice a day to get to and from his work. We stood on the Vincent side while Daddy pointed out the various structures going up on the Childersburg side.

I had never seen such a fast-moving river, had only waded in shallow creeks prone to dry up when the weather grew hot. Nor had I ever watched men wearing hard hats and carrying metal lunch boxes leave their parked cars and stand quietly on a rickety-looking ferry that expelled them, laughing and talking, on the other side. I've never forgotten the sight.

Our new home was fully wired and I marveled at the wonder of light bulbs dangling from the ceiling, the sudden blinding light that bathed each room of the yellow bungalow at the pull of a string I was too short to reach. Yeah! No more smelly kerosene lamps.

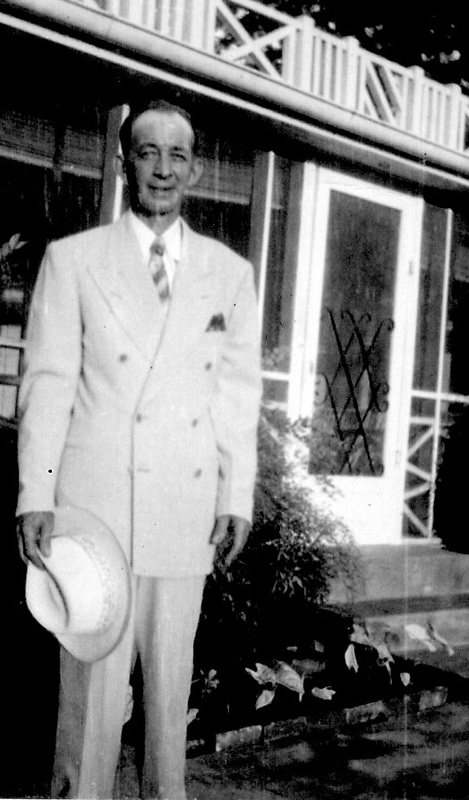

Daddy had been promoted to foreman right before we moved, and he took great pride in his work. The men working under him called Daddy "Fireball", because of his reputation for hitting the ceiling if any of his men slipped up. When an electrician did something stupid and his work failed to pass inspection, Daddy would get hopping mad and his coworkers learned to steer clear of him until he cooled down. The worker responsible for his rage would hide for the rest of the day. I inherited Daddy's explosive temper, but it takes a lot to make me mad and I get physically ill when I do.

One day Daddy came home from work with both hands bandaged and had to stay home until his electrical burns in the palms of his hands healed. While working up on a ladder, he'd grabbed a wire that wasn’t supposed to be "hot". Five thousand volts of electricity surged through his body. He'd had to kick the ladder out from under him and the weight of his dangling body jerked his hands free of the hot wire. He fell fourteen feet to the concrete floor and escaping with only third degree burns. The palm of one hand was burned to the bone, and his voice shook when he talked about it. I stayed right by his side for days, offering him water, and lighting his cigarettes. Gallons of coffee a day and hand rolled cigarettes were his only vices.

That winter the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and President Roosevelt declared war on them. In those early months of World War II the war caused few changes in our lives until the government pushed up the completion date for the DuPont plant. We'd soon need to move.

Things were looking up for him and Daddy wanted a permanent home for his family. My parents decided to move back to the city so Mamma would be near relatives she could call on for help if needed when Daddy took work out of town. He worked out a deal with a distant cousin of Mamma’s, promising to make monthly payments on the three acres they lived on and that Mamma would provide any needed care while the three elderly relatives lived out their lives in their house on what would become our property. No payments to the bank and no risk of foreclosure by the relatives, a win-win situation for Daddy.

That's how he became the proud owner of three acres with a rickety old house the cousins live in and a no-longer-used but sturdy barn. Before his house plans discovered civilians could no longer buy lumber -- it was needed to build barracks on the military bases springing up all across the country. Where could we move?

One Sunday afternoon he and Mamma took us to "look over Daddy's acres". He kept walking in and out of the barn with a ruler in his hand and taking notes with the pencil he kept stuck behind his ear.

I can still picture him stepping out of the barn door with a pleased grin, his everyday Panama straw hat -- the previous year it had been his best hat -- shoved back on his head. "Sugar," he said to Mamma, "I think it'll do. The tin roof is still in good shape, and with a little hard work we can replace these barn doors with a good solid front door and lots of windows. I'll have to do the remodeling with used lumber, but I think I can turn this barn into a home we'll both be proud to show off." Then he walked down the far side of the barn, pointing out the place he'd cut a hole for a window above the kitchen sink.

Six-by-six inch beams supported the tin roof and Daddy stepped off how many smaller ones he'd need to support the floor and walls and scribbled the number on his notepad. "I'll put a bedroom window for us where the barn door is," he said, drawing plans for our new home in his head. I didn't doubt for a minute that Daddy could convert that old grey barn into a nice place for us to live.

Daddy could do anything.

PS: He raised 4 children in that converted barn, and after 30 years built Mamma a new redbrick house where the cousins' house once stood. One of the cousins managed to live for twenty-eight of those years.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed