On Sunday nights at Training Union, Mrs. Austin taught my class of twelve-year-olds, Mr. Austin those already thirteen. After numerous failed attempts, the girls finally convinced the leaders to chaperone a joint swimming party at Robinwood Plunge for us on a hot Saturday afternoon in July. While Baptist boys and girls didn't usually swim together, this would be the girls' big chance to show off in a bathing suit.

When we arrived at the pool Mr. Austin called us to gather around and asked, "Can all of you swim?"

Once or twice each summer I'd meet my friends at the Country Club and spend the day in the Club's public pool, for me a five mile bike ride each way along a busy highway, but I hadn't been to the pool often enough to risk taking a breath with my strokes.

To make matters worse, my underweight body had no natural buoyancy. I couldn't float. My friend Janet had tried to teach me. She'd instructed me to just lie back in the water and relax and promised to catch me if I started to sink.

I always sank. I had small bones and no fat, nothing to keep me afloat, and always sank. I'd learned to hold my breath forever and do the breast stroke across the deep end of the pool before coming up for air. I felt comfortable at the bottom of the pool, where I liked to hold my breath for a long, long time and listen to the sound of bubbles escaping from my bathing cap. Sometimes I'd pretend I was a deep sea diver searching the bottom for pearls.

It required all my will to keep from telling Mr. Austin I couldn't swim. If I did, I'd be relegated to the little kids' end of the pool, not the best place for me to attract Harold's attention or one of the other boy's so I kept quiet.

When no hands went up, Mr. Austin said, "Good," and rattled off a list of rules, then sent us to dress in our bathing suits. The strong smell of bleach in the girl's dressing room burned our noses so we hurriedly stepped into our bathing suits. With our suits in place and our hair either braided or fluffed around our shoulders we strolled out of the dressing room feeling exposed and shy.

For a while the girls just sat on the edge of the pool watching the boys do cannonballs all around us and splash water in our eyes. Then Janet slid into the water and ducked her head to wet her long hair. It floated out behind her. "Come on in. The water feels good," she assured me.

Harriet and Loretta held hands as they stepped off the last step and water crept up to their waists. I couldn't stand to get wet gradually so I asked Janet to stand under the end of the diving board and show me how deep the pool was there. If I jumped in with enough force to kick off the bottom I would pop right back up to the surface like a cork.

Where Janet stood, the water only came up to her chest. I usually walked out to the end of the diving board and jumped in feet first, Instead, I lingered on the side dangling my feet, hesitant to get wet.

Somebody called me chicken and that's all it took. I marched right out to the end of the board, too self-conscious to take a good bounce and simply stepped off, my arms straight at my sides. I sank like a stone.

Why hadn't I jumped? I was taking far too long to reach the bottom and when I did, the bottom felt uneven, the water much deeper than I'd expected.

Is Janet that much taller than me?

I kicked off the bottom, but not as hard as I needed to. Only one of my hands broke the surface of the water, not my face as I'd hoped. I didn't get the chance to fill my lungs, and I promptly sank again.

I'm in real trouble. What a silly fool I'd been, all because I hadn't wanted the boys watching me jump in. Now I prayed that someone had watched my jump. If my feet couldn't touch the bottom, I wouldn't be able to push off. I had no way to rocket back to the surface the way I usually did and suck needed air into my lungs.

Desperate, I pushed off the bottom, hard, yet failed to break the surface. I began to sink again. Bubbles rose all around me.

This time I kicked really hard, raised one hand out of the water, made what seemed to me like a big splash, but slowly lost what ground I'd gained and began once more to sink.

The harder I tried to reach the surface, the deeper I sank. The next time around I finally broke out of the water and opened my mouth to yell. Too late. I swallowed a mouth full of water and went under again. Tiny bubbles escaped from my bathing cap in a diminishing stream.

The weight of the water pressed me down, down, down and I settled on the bottom. Above me, dozens of legs -- some thin and some long and hairy -- performed a graceful water ballet. The bright light at the surface hurt my eyes.

All the fight went out of me.

Bits of conversation reached me, and laughter. Would I ever have a reason to laugh again?

Hey, can't you see I'm dying down here? I wanted to yell, longing to safely be back up there with my friends. I silently promised God if He let me, I'd never again be ashamed to cling to the side of the pool.

What if no one misses me until the party is over? For me the party was nearly over.

What would Daddy think when nobody brought me home? Would he be mad at me, or would he blame my friends for my demise?

This isn't their fault. I should never have stepped off that diving board.

A single bubble escaped my bathing cap and I squeezed my eyes shut to hold back my tears as the chlorine-laced water cradled me at the bottom of the pool, gently rocking me in the ghostly quiet.

Then I heard Mr. Austin tell Harold he'd seen my hand come out of the water and thought I might be in trouble.

"I am, I am," I wanted to yell, but words wouldn't form.

I heard a splash, was cradled by the slap of disturbed water and waited for strong hands to take hold of me. Another splash, another jolt, and long arms yanked me off the bottom. A hairy elbow forced its way beneath my chin. I sliced through the water as my rescuer easily dragged me back up to the surface I had tried so hard to reach by myself.

Rough hands pulled me out of Harold's arms and shoved me face-down on the hard concrete. Someone hit me on the back. Hard.

Ouch! Take it easy.

"Nothing," a distraught male voice said.

"I'll try artificial respiration," said whoever was kneeling over me.

Harold? How could I ever face him after this?

He forced my shoulders down against the concrete, made my ribs hurt as he pressed hard on my back. I heard every word spoken over me, everything said about me, and felt the same frog in my throat Janet had in hers when she whispered, "Did she drown?

"I doubt she has been under long enough for that," Mrs. Austin assured her, then asked "Has she?" in a shaky voice.

"Only a minute. Maybe a little more," Mr. Austin replied gruffly.

A minute? It seemed like hours to me.

Harold pressed on my back, counting, "One, two, three, four. Rest, two, three, four." And again.

Though I heard every word spoken, much as I wanted to, I was unable to answer their questions or open my eyes.

Suddenly I was floating above them, looking down on my friends beside the pool, interestedly watching their desperate attempt to save me. No matter how hard I tried I couldn't shout "Don't give up on me. Not yet. I hear you. I'm not ready to die."

I prayed long and hard Harold would keep trying to save me. The rest of my life still lay ahead. I'd just discovered boys and still had a lot to learn.

Please don't stop, I kept thinking. I want to go to college and become a teacher. Be a writer. There was so much I still wanted to do. My life couldn't end now. Daddy would miss me too much.

Why me, God? Have my youthful sins finally caught up with me and You are calling me home?

Then I felt the urge to cough. I did, over and over as water gushed from my lungs and spurted out my mouth, burning my throat and strangling me as I tried to gulp in air. I couldn't stop coughing. Tears filled my eyes. Although my lungs were on fire, being able to breathe again felt so good I didn't have it in me to complain and struggled to sit up.

Mrs. Austin wrapped me in a towel and insisted I sit out the party on the side of the pool with only my feet in the water. I had no one to talk to and nothing to do but relive the terrible moments when I'd felt sure I was going to die.

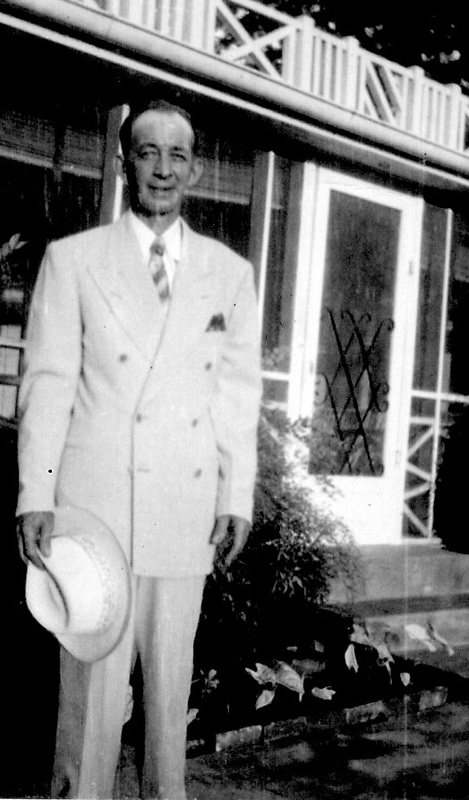

Mr. Austin reported my near-death experience to Daddy, who then calmly laid down the law to me. No more stepping off the thirty-foot diving tower at the Country Club. No more pretending I could swim when I couldn't. He didn't mention swimming lessons. We couldn't afford them, but he did say, "Next time, think before you leap."

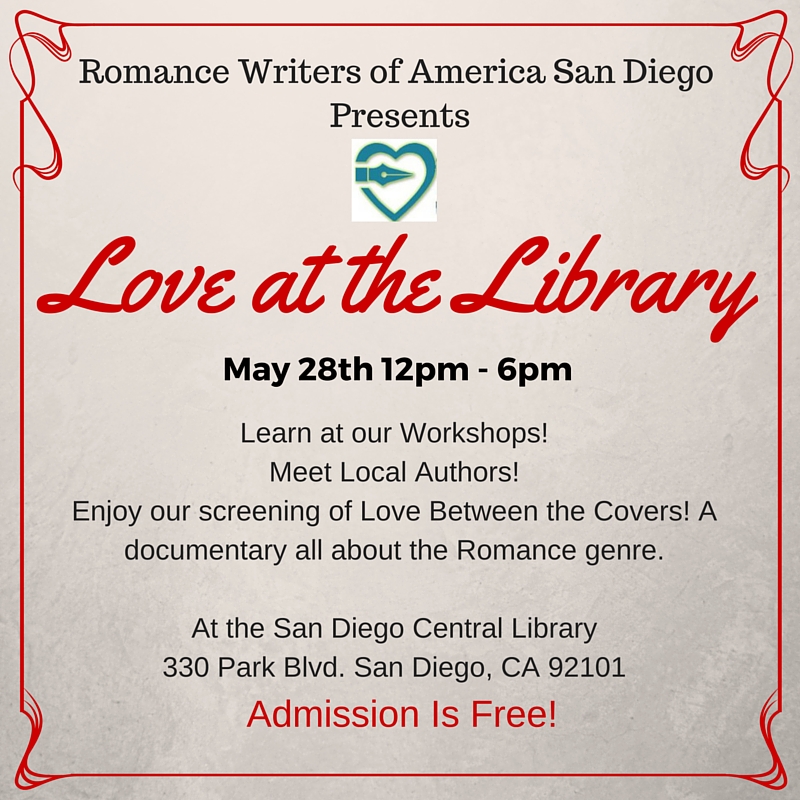

This is from my unpublished memoir "Why Not Me?"

*****

A Reminder: Waterproof your children. It's never too late.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed